AFA Conservation 2024-2025

The AFA has partnered with Harrison’s Bird Foods to assist wild parrot conservation projects taking place in the native habitats. To apply for a small grant, send project information and funding requests to: AFAoffice@AFAbirds.org

Thank you for Harrison’s Bird Foods for their support and generosity.

Be sure to support our Conservation Partners. Click the logo to shop at Harrisonsbirdfoods.com

Representatives of Harrison’s Bird Foods present AFA CFO Janice Lang with a check for $25,000.

Become an AFA Conservation Partner

You will be recognized in the AFA Watchbird Journal and on the AFA website in our Conservation site pages. Interested persons or organizations should contact Rick Jordan by email at AFAOffice@AFABirds.org.

Current Projects:

(Partial funding and support contributed by the members of the American Federation of Aviculture, Inc.)

The AFA continues to seek out important research, conservation, or field biology projects that may benefit from our financial assistance. The AFA Conservation committee reviews inquiries or applications each year and decides on the projects that are a good fit with the “mission” of the American Federation of Aviculture, Inc.

Below is a list of links to information about current AFA Conservation projects . Please take a minute to familiarize yourself with these projects and their goals, and please donate to the AFA so that we can assist these projects and others this year. If you have information on a project that may benefit from AFA’s assistance, please visit our pages explaining How to Submit a Conservation Grant Proposal and the Grant Proposal Submission Form, and then contact Rick Jordan by email at AFAOffice@AFABirds.org, or write to The American Federation of Aviculture, Inc. P.O. Box 91717, Austin, TX 78709.

Chajul Biology Station, Natura Mexicana, Chajul, Mexico. The official 2019 AFA Conservation Project has been working to save wild scarlet macaws in the Lacandon rain forest of southern Mexico. Due to poaching for the local and international trade, nest production of wild scarlet macaws in this area is near a zero percent fledgling rate without intervention. Biologists at the Chajul station monitor wild nests, identify hatchlings, or rear and release wild-hatched scarlet macaws back into the forest. The program is experiencing very high success rates and has “fledged” over 150 scarlet macaws back into the wild. The station biologists need equipment such as brooders, incubators, portable incubators, gram scales, and various medical supplies. The goal for the 2024 fund raising season is $5000 to assist this project to procure the needed equipment and supplies.

Selva Maya Living Landscape Program, Wildlife Conservation Society-Scarlet Macaw Chick Survivability Research-Guatemala Since 2002, the WCS has been working to further the understanding of the conservation status and to address key threats to scarlet macaws and their habitat in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. In recent years, they have implemented a mix of threat-based interventions and direct population enhancements to increase population recruitment through new experimental interventions designed to increase chick survival. Scarlet macaws remain one of the top five landscape species of WCS’s Selva Maya Living Landscape Program.

Prevention protocol to protect parrot nest boxes from colonization by Africanized honey bees,

Principle Investigator: Caroline A. Efstathion

From Abstract: We have developed a preventive method, called push-pull that repels home seeking scout bees from parrot boxes with a bird safe insecticide, permethrin, and simultaneously draws them to pheromone baited traps. Providing additional sites for bees to nest that are more attractive to their needs (small entrance opening, bottom entrance and south facing entrance) than bird nest boxes, along with the attracting pheromone nasonov, bees are more likely to choose these boxes as homes over bird nest boxes. So far we have worked with several locations to address this problem (primarily with psittacines) using whatever donations we can obtain. Since we will be writing papers explaining our successes and describing our protocols, we anticipate eventually our method will become well known and others will begin to apply it without needing our assistance. Until then, we need to find funds for our anti-bee invasion projects.

Investigation of Wild Parrot complete blood counts and causes of death in the Tambopata Region, Peru

Principle Investigators: J. Jill Heatley, Lizzie Ortiz-cam, Donald Brightsmith

From Abstract: Electrolytes, venous blood gases, lactate and ionized calcium are determined bird-side in the field with an i-STAT analyzer. These data will provide invaluable physiologic baseline data for the growing nestling macaw and the adult free-flighted parrot. Simultaneously, birds are evaluated for health via complete blood count and differential white blood cell determination and examined for external and internal parasites. As in other areas, the overlay of basic biological data (age, gender, mortality, growth rate) provided by biologists at this site should information directly applicable for use in the avian veterinary practice while also provided guidelines for conservation biologists in assessing parrot population and individual health. Additionally, the reasons for clay lick use still remain theoretical. The possibility that birds visit clay licks for necessary electrolytes is one theory which may be investigated though serum electrolytes determinations when data such as crop contents, bird age and reproductive status are considered together. Results may be useful in formulating appropriate rations for companion avian species. We are in need of funding for a dedicated student worker trained for determination of white blood cell counts from the slides which have already been transported from Tambopata. We have over 100 samples in which to count the differential. Electrolytes and venous blood gases have already been determined.

Lear’s Macaw Corn Subsidy Program: Working with partners to supply farms in Brazil with corn that are losing crops to the wild Lear’s macaws.

Tambopata Macaw Project: Assisting in the funding to collect nutritional, nesting, behavioural and general ecology data on macaws in the Tambopata preserve, Tambopata, Peru.

AFA Conservation

Past Projects

AFA has a long history of funding medical and husbandry research, including psittacine conservation projects designed to better manage and save endangered species in the wild. AFA promotes population management and cooperative breeding programs to ensure the long-term survival, health and genetic diversity of parrots and other birds in captivity.

Recent grants include:

- The red-fronted macaw conservation project (Asociacion Armonia, Bolivia);

- Project Abbotti, conservation of the recently rediscovered Abbotti’s cockatoo (Indonesian parrot project/ project Birdwatch);

- The spix macaw project, captive propagation in Brazil;

- Nesting ecology of the slender-billed conure;

- Proventricular dilatation disease research (Schubot Exotic Bird Health Center, Texas A&M University);

- Puerto Rican parrot (PRP) reintroduction;

- A joint project with the Loro Parque Foundation in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain on artificial nest boxes for the Catey, or Cuban parakeet.

Past conservation grants have helped promote:

- The breeding biology of the Bahama parrot;

- The status and conservation of the cape parrot in southern Africa;

- The ecology and breeding biology in the conservation of the yellow-shouldered Amazon on Margarita, Venezuela;

- A preliminary study on the impact of Hurricane Gilbert on the psittacine population of Yucatan;

- Macaw conservation in Belize and Honduras in Central America; natural history of the el oro parakeet (Pyrrhura oresi);

- Determination of the status of the glaucous macaw and hyacinth macaw in Argentina and Paraguay;

- The genetics of the Puerto Rican parrot (Amazona vittata);

- Support for the Centro para la Conservation de los Psitacidos Mexicanos;

- First workshop of the management and conservation of macaws in meso-America;

- Halfmoon conure breeding consortium;

- Tracking of seasonal movements of the great green macaw in the Atlantic rainforest of Cost Rica and Nicaragua; among others.

Additionally, more than 40 separate grants have been awarded between 1982 and 1993, to proposals in avian research.

AFA Conservation Grant Proposals

We appreciate your interest in theAmerican Federation of Aviculture, Inc. (AFA). The purpose of this document is to provide you with information about the required procedures to follow when requesting funding from the Avian Conservation Grants program. The mission statement of the AFA and a brief history of the organization will help you understand the types of projects we support. Please review the following proposal guidelines. Note AFA generally provides modest grants of $500 or less annually, except under exceptional circumstances when we have been contacted in advanced and approved submission of larger grants or in cases where the committee awards larger amounts based on the submission goals and objectives.

Mission and Purpose of the American Federation of Aviculture (AFA)

“The mission and purpose of AFA shall be to promote the advancement of Aviculture through educational programs that support the advancement and improvement of breeding practices, husbandry practices, and living conditions for exotic birds, conservation, research and legislative awareness.”

AFA believes holders of exotic birds need to be aware of the special needs of the species they hold, be aware of their conservation status, up-to-date research findings enhancing the well-being of the birds, and the state and federal regulations pertaining to exotic birds.

AFA History

During an outbreak of Exotic Newcastle Disease in California, in the early 1970’s, thousands of perfectly healthy exotic birds in private collections were euthanized by the USDA. As a result of the outbreak State of California proposed legislation that would narrowly restrict or ban the ownership of exotic birds was introduced. This proposed legislation to restrict private ownership was the catalyst that brought many Southern California bird owners and clubs together to form the AMERICAN FEDERATION OF AVICULTURE, INC. in March of 1974 to serve as an avicultural umbrella organization.

The AFA is a non-profit 501(c)3 educational organization incorporated in the state of California, (business office located in Austin, TX) with a membership base of individual members both nationwide and worldwide. The AFA is also a federation, comprised of numerous affiliated bird clubs and organizations representing thousands of aviculturists.

The AFA is dedicated to the promotion of aviculture and the conservation of Avian Wildlife through the encouragement of captive breeding programs, scientific research and the education of the general public. To promote the interests of aviculture , the AFA works to educate legislators within the U.S.A. The AFA also represents the avicultural community at CITES meetings.

Avian Research Grants

A goal of AFA is to ensure long-term, self-sustaining populations of exotic birds both in captivity and in the wild. In support of this, AFA provides small grants targeted to projects that have a good likelihood of success and of providing useful knowledge on birds. Projects may be in a variety of areas with captive and/or wild birds, including veterinary medicine, captive husbandry, conservation, equipment, behavior, or education. The key objective must be to contribute to the goal of ensuring the enjoyment of birds by present and future generations.

Procedure

- Proposals may be submitted by email (preferred) to afaoffice@afabirds.org or 2 copies may be sent by postal mail to:

American Federation of Aviculture, Inc.

PO Box 91717

Austin TX 78709-1717 - Deadline for proposals for funding in a particular year is receipt by the AFA office by September 15 of the previous year except under special circumstances. It is recommended that proposals be submitted during the July-August timeframe. Electronic submission in MS Word or pdf format is preferred. Late proposals will be considered, but funding may not be available until the following year.

- An acknowledgment of receipt of the proposal will be sent to you within 3 weeks of receipt. Please contact us if you do not receive an acknowledgment.

- In November of each year the Avian Conservation and Research Grants Committee will make recommendations to the Board of Directors for consideration of funding to be disbursed in the following year. The Board of Directors will approve suggested programs at their November budget meeting. A different time frame may be approved in advance by the Board (contact the chair of the Avian Conservation and Research Grants Committee).

- Recipients of grants will be notified by email, letter, and/or phone by 15 November.

Guidelines for Funding

Please read the following restrictions and guidelines for AFA Avian Research Grants. Although not all are requirements, preferential consideration will be given to projects that meet them.

- Funding will generally be considered for US 501(c)(3) non-profit entities or individuals associated with these entities or the equivalent in a non-US country.

- Recipients must be able to receive the award by a check in $US made out on a US bank

- AFA Avian Research Grants ordinarily will not exceed $500. Please take this into consideration when submitting a proposal. Exceptions require prior discussion with the chair of the Avian Conservation and Research Grants Committee.

- All proposals must involve humane and respectful treatment of animals.

- Proposals considered shall be “culturally appropriate” for the targeted area (country, state, region).

- Funded projects must agree to submit a six-month progress report and then a final report at the conclusion of the funded year. These may be brief but should demonstrate the progress and then outcome(s) of the funded project. No-cost time extensions of the grant may be requested and will be given if appropriate.

- International proposals may be asked to submit a letter of endorsement from the government of that country.

- Final funding decisions are contingent on a majority Board vote and available funds.

- The AFA Board reserves the right to make exceptions to any of the above guidelines.

Deadline for submission: September 15 for funding in the following year. Exceptions by prior arrangement only.

Recommended Outline

To apply, email a copy of your proposal to afaoffice@afabirds.org. (MS Word or pdf preferred) or 2 printed copies may be sent by postal mail to:

American Federation of Aviculture, Inc.

PO Box 91717

Austin TX 78709-1717

Put all the information on the enclosed project proposal title page on the first page of your proposal. Cover the following items in the body of your complete proposal. Generally 1-6 should not take more than 5 pages and possibly less (be brief).

- Background Information on Organization

- Introduction

- How does this project fit in with the AFA mission statement?

- Project Description and Justification

- What are your overall goals?

- Specific objectives

- Methods

- Project design and implementation

- Animal handling and methodology (if applicable). (This item should include detailed information on all animal handling and captive maintenance planned, including but not limited to: animal immobilization, capture techniques, collection of crop or cloacal contents, blood or tissue collection, banding or tagging, and radio-telemetry devices.)

- Local community involvement/professional development (if applicable)

- Education/public information (if applicable)

- Expected Results

- How do you propose to measure and quantify your success?

- Benefits and/or Impact

- How will your work make a difference for wild or captive birds?

- How do you plan to disseminate project results?

- How will you let others know that AFA helped with support to your project?

- Describe any post project continuity or additional work.

- Project Timetable (Limit 1 page)

- Budget (Limit 2 pages)

- Outline the budget for one year

- List matching funds and sources or associated funded projects that may provide synergy with the proposed effort.

- Vitae of Principal Personnel (Brief-no more than 2 pages each; preferably shorter)

Please be as concise as possible. Some sections may not be applicable to your funding request.

Click here to download these submission guidelines in printable format.

Click here to download the project proposal submission form.

Legally Import Birds – Cooperative Breeding Programs

By Mary Ellen LePage, AFA Committee Chair and Program Leader for the Cooperative Breeding Program

Importation Law

The Wild Bird Conservation Act (WBCA) of 1992, restricted importation of any species now listed on any appendix to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), even though some species are not really endangered. This law was enacted to stop the capture and importation of birds for the U.S. pet trade. Importation without a permit is not allowed for birds listed on CITES appendices.

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) International Affairs (Management Authority) is responsible for administering CITES for the United States. They issue permits to import and export species that are protected by CITES and by various other wildlife conservation laws, such as the Wild Bird Conservation Act. They administer the Cooperative Breeding Programs for importation of live exotic birds.

Cooperative Breeding Programs

Cooperative Breeding Programs (CBPs) allow limited importations of certain species for use as breeding stock. The intent of the CBP is to import species of birds that are not well represented in the United States, and to import them in sufficient numbers of diverse genetic backgrounds to support a sustainable population in the U.S.

A Cooperative Breeding Program consists of a Leader/Program Manager, and two or more breeders (which may include the leader), that must be willing to comply with the USFWS regulations, and the requirements of the overseer. The leader submits an application to USFWS for a Cooperative Breeding Program, specifying an avicultural group that will oversee the CBP. AFA has been the Overseer for the following past CBPs – Red Siskin, Blue-headed Macaw, Javan Hill Mynah, Pyhurra Conure, Red-crested Cardinal and is the current Overseer for the Blue-eyed Cockatoo CBP which has been extended to include most of the Black Cockatoos. The Pyhurra Conure CBP has been extremely successful at populating the US with the species.

USFWS Approvals

The USFWS approves:

- • the request for the program, as submitted by the Program Leader,

- an overseer for the program,

- each member allowed to be in the program, and

- the importation permit for each bird or group of birds to be imported.

USFWS Requirements

USFWS requires that imported birds be domestically raised in a country not their origin. Importation of CITES I species are only rarely allowed and require a special breeding facility. So that birds may not be imported just for sale, USFWS requires that the birds be imported only by breeders, for breeding purposes, and that they may only be moved to other members of the program. When imported birds are to be transferred to a new owner for any reason, that owner should become a member of the CBP. USFWS also requires biannual updates of the program.

Pros and Cons of CBPs

The benefit of these CBP is that we are allowed to import species of birds that are underrepresented in US aviculture, and thus increase our genetic pool of these species.

The problems have been the difficulty in identifying birds to be imported, and the possibility of being scammed.

Current Ophthalmica (Blue-eyed) Cockatoo CBP

The Blue-eyed Cockatoo CBP, submitted by Susan Clubb DVM, was approved in 2005 and 9 pairs of Blue-eyed cockatoos have been imported since that time. Imports were young and are currently just reaching breeding age. Two pairs have laid eggs.

When I submitted the renewal of the CBP to USFWS, I requested that the permits be extended to cover all the black cockatoos. We are now permitted to import the Gang-gang, Red-, White- and Yellow-tailed Black, and Glossy Cockatoos. Palm Cockatoos are CITES I therefore importation is not allowed.

The membership of this CBP is still open. If you want to join the CBP and import some of these magnificent birds, contact Mary Ellen LePage maryellen.lepage@gmail.com.

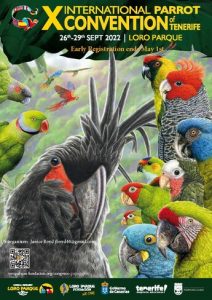

Want to Learn More About Parrot Conservation?

Attend the International Parrot Conference in the Canary Islands.

For more information, contact: Dr. Janice Boyd (jboyd46@gmail.com)

poster X Congreso de Papagayos FEB 2022_ING-jdb-com

All About CITES

The purpose of the AFA CITES Committee is to monitor or participate in the CITES meetings, CITES animal’s committee meetings, and/or to assist the USFWS when information about the trade in parrots or their keeping and breeding is needed. Since CITES is set up in tiers, much of our “ground-level” experience is first offered at the CITES animal’s committee level. It is surprising how often aviculture’s opinions on Psittacine issues is agreeable to that of the USFWS, and frequently their proposals parallel our concerns on the same subjects. In the past, the USFWS has granted the AFA official NGO (Non-governmental observer) status so we can attend animal’s committee meetings and provide input. As well, the chairman of the animal’s committee has frequently extended an official invitation for the AFA committee chair to attend the meetings. This IS “our” voice to those that govern the trade in birds and animals on an international basis.

What Exactly is CITES?

- The term “CITES” stands for “Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species”.

- CITES is an international “treaty” that went into force in July of 1975. The aim is to ensure that international trade in certain species of plants and animals did not threaten their existence in their native habitats. Today more than 30,000 species are afforded various protections under the treaty, ranging from live specimens of Panda bears to fur coats or alligator wallets. In the case of aviculture specifically, the treaty governs the trade in live birds that are traded from one country to another, regardless of their origin of captive-produced or wild-taken. The signatories (attending member countries) of the treaty have vowed to honor the “regulations”, called “resolutions”, put forth under the CITES Convention.

- Today over 150 countries (Parties) worldwide have signed onto and vowed to honor the Treaty. Each country then assigns its own governmental agency that will monitor the Convention and enact any protections that are “passed” or “agreed” at the Convention of the Parties (COP). In the United States, the President has assigned the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) as our representative to CITES. This makes the USFWS responsible for upholding the rules of the treaty and to make sure the United States abides by any “resolution” (Agreed rule) of the Convention. As well, our USFWS is the official U.S. governmental voice to the treaty. There may be other U.S. groups attending or even presenting information or suggestions, such as the AFA, HSUS, WPT, and others, but these organizations are not the official U.S. governmental voice.

- As eluded to above, in addition to governmental Parties, others, called “Observers” or “Non-governmental Observers” (NGOs) may attend the Convention or the subcommittee level meetings to present information to the governing Parties. The purpose of these NGOs is to offer scientific data about the species or genera with which they have expertise. The American Federation of Aviculture, Inc. has acted as an official Non- Governmental Observer to the Convention. The AFA CITES Committee chairman provides input and makes comment to the USFWS with regard to avian species and the International trade of birds worldwide. If attending a CITES committee level meeting, the AFA representative may be given a chance to stand and present such information directly to the CITES Committee Chairperson as well. This is why we need breeding data and census data of all birds kept in captivity, and any trade data that may be important to present the entire picture of the status of a species.

- Keep in mind that CITES is an international treaty, and that their solutions put forth at the Convention go to the many participating countries to, in turn, be incorporated into their national domestic laws. Although CITES cannot and will not get involved with domestic law or trade, its many resolutions must be used by all participating countries when they issue permits or participate inany international movement or trade of listed species. For example, CITES may list the Moluccan Cockatoo as CITES Appendix I, indicating that international trade in this species must be of the utmost importance or else it is not permitted. Yet the U.S. may not use this rule internally, and may not require permits or special findings when the same species is sold or transferred from one State to another. CITES is an international rule making body.

- CITES listings, the lists of the actual plants and animals that are afforded certain protections by the Convention, are divided into three “Appendices”. These appendices are conveniently numbered as Appendix I, Appendix II, and Appendix III. Those species listed on Appendix I to the Convention are the most critically endangered in their native habitats,where as those listed on Appendix II may require close monitoring or “quota systems” if subjected to international trade to prevent them from becoming endangered. Appendix III is a list where each individual country can place a species if it has concerns about trade within or from its own country. All parrot species except the ring-necked parakeet, cockatiel and budgie are listed on CITES Appendix II as a precaution and due to the possibility that trade may take place unmonitored. In the recent past ring-necked parakeets were listed on Appendix III by Ghana (apparently due to internal trade issues), but have recently been removed and are now Non-CITES. This means that currently any Rose-ringed (ring-necked) parakeet can be imported and exported internationally without CITES permits. As far as CITES is concerned, a certificate of origin is still required from a governing CITES government to demonstrate that the birds originated in the exporting country. Of course there are also national laws that may require permits to import such species. In the U.S. there is also a USDA quarantine requirement for all exotic birds imported into the U.S.

- Listing criteria for a species is based on its “range” in the wild, NOT on its populations in captivity around the world. This is often very frustrating for aviculturists as they do not understand why a supposedly “common” bird would require special permits for export from one country to another. A good example of this would be something like the “Scarlet-chested parakeet” which is listed on CITES Appendix I due to its status in the wild. Yet, here in the United States, and virtually across the world, Scarlet-chested parakeets are very common and breed readily in captivity. So much so it seems that our own USFWS has removed the internal Endangered Species permit requirements for interstate commerce with this species. Their listing under CITES is to protect any further removal of this species from the wild. It has nothing to do with the successes of aviculture or the current status of this species in our aviaries.

The Difference Between CITES and the US Endangered Species Act

- Many aviculturists are confused about our wildlife laws and how they “interact” with each other. One of the most confusing points is that CITES Appendix I listed species are not always “US Endangered Species”. This is because the US ESA orUnitedStates Endangered Species Act protects or lists species that meet certain criteria, not necessarily the same as the criteria to list them on CITES Appendix I.

- Many of the larger macaws are listed on CITES Appendix I, and therefore their International trade (commercial) is prohibited except as captive-bred birds coming from aCITES approvedfacility. CITES Appendix I includes the Spix’s macaw, Lear’s, Scarlet, Military, Buffon’s, Blue-throated, Hyacinth, Red-fronted, Blue-headed, and Illiger’s macaws.

Yet the U.S. ESA does not include all of these same macaws. To date the ESA lists only the Spix’s, Lear’s, Blue-throated, Buffon’s, and military macaws. So, for all intents and purposes here in the United States, no federal level permits are required to own, breed, or sell the ESA listed and CITES listed species. But, some States use the ESA federal list as their own internal State list of restricted species, and if you live in such a State, you may be breaking the law simply by owning a species listed on the federal list. Any shipping or international movement requires permits from both the federal and CITES level management authorities. The USFWS is working on incorporating many of the CITES resolutions into our domestic laws for the future and we must keep an eye on the regulations to make sure that these commonly kept and bred species are not restricted internally within the United States and/or on a State by State basis. The American Federation of Aviculture, Inc. monitors the Federal Register for any pending legislation that would affect bird keeping here in the U.S.

- Currently the United States Endangered Species Act includes the following parrot species (often found here in aviculture) and any movement across a State line that involves money or commerce would require federal permits. To loan or donate one of these species to another breeder in another State, or within your own State does not require the federal permit, but may require a State permit depending on which State you live or plan to move the bird to. NOTE: All of these species are also listed on either CITES Appendix I or II and would require US Federal and CITES permits to ship in International Commerce.

(US Avicultural species listed on the US Endangered Species Act) Vinaceous, Red-browed, Puerto Rican, Red-necked, Red-tailed, St. Vincent’s, and Cuban amazons. Golden and Blue-throated Conures, Thick-billed parrots, Pileated Parrots (South American), Golden-shouldered parakeets, Red-vented cockatoos, Lesser Sulphur-crested and citron-crested cockatoos, and Military, Buffon’s, and Blue-throated macaws. Recently more species have been added to this Act, some have been exempted from federal interstate commerce permit requirements due to their pet-trade popularity here in the U.S. but may still be illegal in some States. These include the Moluccan cockatoo and the Umbrella cockatoo.

- Even though we call many of the parrot species now found on CITES Appendix I, Endangered, for our purposes here in the United States, with the exception of the short list above, they are not regulated unless we plan to ship them across an International border (yes, even Canada or Mexico). The list of CITES Appendix I parrots is extensive and includes many of the birds we breed and sell into our domestic pet trade. For a complete list, you can contact the USFWS in Washington, at 800-358-2104, or visit www.cites.org.

Some of CITES Resolutions Pertaining to Parrots

- Parrots are an important focus under CITES. Literally every meeting of the Parties involves some discussion about parrots and their International trade under the treaty. The many NGO groups provide data pertaining to parrots in the wild, and the current status of their habitats and numbers. Many of the NGO groups that attend would be familiar to bird breeders. Some of them include the North American Falconer’s Association, The Humane Society of the United States, PETA, Pet Industry Joint AdvisoryCounsel, Save the Whales, Animal Welfare Institute, Environmental Investigation Agency, AFA, World Parrot Trust, WWF Traffic, European Falconer’s Association, and many, many more. These and other NGO organizations contribute their input to each and every discussion regarding the trade in birds and other animals.

- CITES also has subcommittees. The one that would include birds is called the “CITES Animal’s Committee”. These committees are charged with gathering information to be presented at the formal Convention of the Parties. Much of the work that would pertain to the AFA is accomplished at this committee level. Thankfully the committee level is a little more personal than the COP meetings, and it is easier to raise concerns or present information that will then be used to formulate suggestions to the COP Parties.

- One of the most important resolutions affecting parrot breeders pertains to International Trade in Appendix I species that were bred in captivity. The CITES Convention provides for trade in Appendix I species to take place as if they were on Appendix II- if they are bona fide captive-bred animals. On the surface it sounds like something very easy to qualify, however, the Parties have had much trouble defining “Bred in Captivity” in such a way that it would not affect “wild” birds and animals covered under Appendix I. Technically, the definition usedcan notaffect any animal that was taken from the wild. Therefore, the definition that has been adopted eliminates all F1 (first generation captive-bred animals from qualifying because their parents were wild-caught). This way, to qualify as an animal “bred in captivity”, an animal must be F2 (second generation captive-bred) or higher to be considered for trade as an Appendix II listed species. Furthermore, CITES has devised a “system of facility registration” where governmental organizations can verify that animals are actually being bred to the second generation. Unfortunately, the rules under these resolutions have been so confusing and so rigid that there are only a handful of registered bird breeding facilities that have even registered for this exemption under CITES. The whole system is in need of review and hopefully will be changed at some point in the future.

- Another subject of heated debate at these meetings is the term “for commercial purposes”. Under the Convention, a government must ascertain whether a facility breeds its animals for “primarily commercial purposes” or whether they are a “non-commercial” entity. After many discussions it has been agreed that unless you breed an animal species for a direct release program or approved conservation program, you are considered a commercial breeder and therefore must qualify under the current registration scheme in order to engage in International trade with an Appendix I species…traded as Appendix II. On the surface this angers many breeders as they often consider themselves as a non-commercial breeder. But technically all breeding is commercially driven unless all offspring are donated back into a conservation program that directly benefits the wild population of the same species. This means that if you have only one pair of Appendix I birds, and you breed them and sell your offspring to other breeders or the pet trade, you are a commercial breeder! Even many zoos are considered “commercial facilities” if they do not participate in “Species Survival Plans” that eventually will directly benefit the species in the wild. Under CITES, the trade in CITES Appendix I species for commercial purposes is strictly controlled.

- Habitat preservation and restoration is not a primary part of CITES and its resolutions at this time. However there have been several important discussions about how the Convention can begin to include such conservation. It will be very interesting to see just how they resolve these issues.

AFA Conservation

Importing or Exporting Birds (United States)

General Information

The legal importation of most pet-trade-type-birds came to a halt in late 1991 when a moratorium to the Wild Bird Conservation Act of 1992 (WBCA) was placed into effect by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). At that time, the WBCA only covered certain families of birds, and only those listed on CITES I and CITES II appendices (CITES is the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered and Threatened Species). But, shortly after its passing, several anti-trade groups came together and sued the USFWS to add all birds listed on CITES appendix III as well; Making the WBCA a virtual “ban” on the importation of specific families of birds, and certainly for the family known as parrots (Psittacines). Information sheets are available on this website explaining each of the above laws in more detail.

Importing under a Cooperative Breeding Program:

The WBCA allows for limited importation of “qualified” species under two exceptions available to breeders in the United States. The first exception is called a “Cooperative Breeding Program” or CBP. Under these programs clubs or aviculturists can come together and design their own breeding program aimed at the establishment or conservation of a species. The participants of this program may be authorized to import certain numbers of the target species under the program to be used as breeding stock to meet the stated objectives of an approved CBP. These imported birds, even if captive-bred in another country, cannot be imported solely for the purpose of resale. The manager of the CBP must file a report with the USFWS every two years giving the status of all imported birds, and the disposition of all offspring produced under the CBP. At that time the USFWS will decide if goals are being met and will either extend the program, or discontinue it. Usually there are quotas set by USFWS under all CBPs so that it is not used as an import mechanism to supply the pet trade with imported birds.

Importing “Exempted” Species under the WBCA:

The WBCA also has a second mechanism allowing the importation of certain species of parrots and pet-trade birds. During the drafting of the law, key avicultural groups showed great concern over the effects that the WBCA might have on the pet trade in the United States. An exception for qualified “captive bred” species was built into the law. This is not to say that any captive-bred bird can be imported into the United States, but instead, the drafters of the law came up with a short list of species that are available in aviculture around the world, and where that species is not being exploited or traded from the wild, and where it is well documented that the species is being bred successfully in aviculture throughout the world. Aviculturists can petition the USFWS to add or remove species based on the listing criteria. But no species that is currently being removed from the wild for trade anywhere in the world would qualify for this list. The current list of species permitted for import as “captive bred” is contained in Title 50: Part 15, Subsection 15.33. You can view the list here. Remember, there are some pet-trade species of passerines or even a few parrot species, that are not listed on any CITES appendices, and therefore can be imported into the United States.

Exporting birds from the United States:

Breeders, or even pet-owners in other countries, may contact a U.S. breeder and ask if they can export a bird for them. Exportation of birds from the United States is controlled by resolutions and rules under the CITES treaty. Exporting species listed on either Appendix II or Appendix III, is possible but the exporter must follow certain guidelines and make sure they apply for, and receive, all the necessary permits and licenses. For those species listed on Appendix I, CITES has a very specific qualifying process whereas the originating breeding facility must be registered with the CITES Secretariat before any of these species enter into “commercial” trade from one country to another. To date there are only a handful of registered breeding facilities around the world producing specimens of a CITES Appendix I species, qualified for legal export. There are no CITES registered or qualified parrot breeding facilities located in the United States at the time of this bulletin.

A Note about the term “Commercial” as it pertains to imports and exports:

The argument over whether a breeder or pet owner is a commercial entity comes up often. This is probably because Miriam Webster and the CITES Treaty have two different definitions for such activities. Nationally, we might only consider ourselves as commercial breeders if we sell baby birds or broker birds for money. But as it pertains to any international movement of birds under the CITES Convention, the term commercial means ANY movement or transaction that is not “non-commercial”. For the sale, trade, movement, or export of any animal listed under any CITES Appendices to qualify as non-commercial, the end disposition of that animal or bird must be to directly enhance the survival of the species in the wild. In other words, if it is not being sent to a conservation project that has direct ties to the conservation of the species in the wild, it is a commercial transaction. Yes, even the loan or gift of a bird from one breeder to another, where neither breeder is involved with the in situ conservation of the species in the native habitat, can be considered a commercial activity.

Exporting Continued:

So, if the bird to be exported from the United States qualifies for export under CITES and the USFWS, a permit can be issued by USFWS. But this is only the beginning of the process! Within the United States there are several agencies that have permits or inspection requirements for an animal to leave the country legally. In addition to the CITES permit for the actual bird to be exported, USFWS also requires that the exporter have an “exporter’s license”. This is often obtainable by applying to the local field office of the USFWS closest to the exporter’s home. Be aware you will be probably be applying for a “commercial exporter’s license” as explained above.

In addition to the CITES permit and an exporter’s license, U.S. Customs also requires a declaration to be filled out and signed designating the export into one of several Customs categories of export. Also, an International Health Certificate is required by USDA and must be signed and sealed by the State of export no more than 10 days before the scheduled airline flight that will carry the bird out of the country. Each importing country also has its own requirements for this health certificate and certain words must appear on the certificate and/or specific tests must be accomplished before they will allow the bird entrance into the importing country.

As if this is not enough, an appointment is required with the local USFWS inspection station where the wildlife can be inspected before it is placed onto the airplane. The inspector will sign an inspection form, and the original CITES permit, which must accompany the shipment. The USFWS only does inspections at certain “designated ports”. Be sure to check for the one closest to you and contact them about an inspection on the day of export.

The legal exportation of a bird from the United States can be frustrating and expensive. Each and every step along the way has administrative costs associated with it. From permit costs, to license fees, to inspection fees, the cost of exporting a single bird can be high. Sometimes it is just best to tell your foreign friends to find a pet bird locally.

Click here to download a printable version of this page.

AFA Conservation

The Wild Bird Conservation Act of 1992 (WBCA)

The Wild Bird Conservation Act of 1992

Signed into law on October 23, 1992, the WBCA was designed to stop the mass importation of wild‐caught birds destined for the U.S. pet trade. Initially this law pertained to only birds listed on CITES Appendices I and II. But a lawsuit brought against the USFWS by animal protection groups extended its constraints to “Any CITES listed parrot species”. Several other “groups” of birds are also protected under this law.

Special Note: Many people think that this import prohibition does not include neighboring countries such as Canada or Mexico. But it most certainly does and fines and imprisonment could result from importing, without a permit, any parrots from these countries as well.

What Does the WBCA Mean to Aviculturists?

Under the act, there are provisions that preclude the importation into the U.S. of any CITES listed bird species not included in the families: phasianidae, numididae, cracidae, meleagrididae, megapodiidae, antidae, struthionidae, rheidae, dromaiinae, and gruidae. It clearly includes the family: Psittacidae or parrots. The USFWS has developed a list of species “exempt” under the WBCA and allowed for importation if they are “bred in captivity” in another country and no known wild specimens are in trade worldwide. This list appears below.

Cooperative Breeding Programs

A cooperative breeding program can be designed by any bird club, group of breeders, or other U.S. citizens that wish to import restricted birds for a breeding or conservation program. The program itself can be designed by the applicant but must be approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. All programs require annual reporting to the USFWS and depending on how they are designed, usually imported birds and their immediate offspring must remain with approved members of the program until the program has reached its stated goals and is disbanded by the originator or the USFWS. The law allows for approval of programs that are:

(A) Designed to promote the conservation of the species and maintain the species in the wild by enhancing the propagation and survival of the species; and

(B) Developed and administered by, or in conjunction with, an avicultural, conservation, or zoological organization that meets standards developed by the Secretary.

Permit Contact: Dept. Of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Management Authority, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr. Room 212, Arlington, VA 22203 or Call: 703-358-2104

Captive‐bred or “Clean list” (WBCA Exempt) Species:

Species not on this “captive bred” list and found on any CITES appendix are prohibited for import except under “approved cooperative breeding programs”. CITES permits or ESA permits are still required for importation of some species.

Arranged alphabetically by Latin Genus.

Agapornis personata, Masked lovebird.

Agapornis roseicollis, Peach-faced lovebird.

Aratinga jandaya, Jendaya conure.

Barnardius barnardi, Mallee ringneck parrot.

Bolborhynchus lineola, Lineolated parakeet (blue, yellow, and white form).

Cyanoramphus auriceps, Yellow-fronted Kakariki Parakeet.

Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae, Red-fronted Kakariki parakeet.

Forpus coelestis, Pacific parrotlet (Lutino, yellow, blue, and cinnamon forms).

Melopsittacus undulates, Budgerigar.

Neophema bourkii, Bourke’s parrot.

Neophema chrysostoma, Blue-winged Parrot.

Neophema elegans, Elegant Parrot.

Neophema pulchella, Turquoise parrot.

Neophema splendid, Scarletchested parrot.

Nymphicus hollandicus, Cockatiel.

Platycercus Adelaide, Adelaide rosella.

Platycercus adscitus, Pale-headed rosella.

Platycercus elegans, Crimson rosella.

Platycercus eximius, Eastern rosella.

Platycercus icterotis, Western (stanley) rosella.

Platycercus venustus, Northern rosella.

Polytelis alexandrae, Princess parrot.

Polytelis anthopeplus, Regent parrot.

Polytelis swainsonii, Superb parrot.

Psephotus chrysopterygius, Golden-shouldered parakeet.

Psephotus haematonotus, Red-rumped parakeet.

Psephotus varius, Mulga parakeet.

Psittacula eupatria, Alexandrine parakeet (Lutino and blue form).

Psittacula krameri manilensis, Indian ringneck parakeet.

Purpureicephalus spurious, Australian Red-capped parrot.

Trichoglossus chlorolepidotus, Scaly-breasted lorikeet.

Click here to download a printable version of this page.

AFA Conservation

The U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1972 (ESA)

Update – Military Macaw and Buffon’s Macaw added to US ESA

Update – Cockatoo Species added to US ESA

The United States Endangered Species Act (ESA)

Signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973, the ESA was designed to protect critically endangered species from extinction. This act was one of many wildlife laws enacted in the 1970’s. The U.S. was experiencing a huge growth spurt and many species were threatened by development and expansion into their habitats.

Recap of Requirements for any listed Species:

- Any sale or barter (raffles, auctions, uneven trades) across a State line requires a federal permit

- Possession or breeding of legally acquired birds (Within your State) does not require a federal permit

- Even trades of like offspring across a State line does not require a federal permit

- Sales within a State does not require a Federal permit

- Advertising listed species “nationally” for sale requires the words “Federal permit required” in the advertisement

What Does the ESA Mean to Aviculturists?

Under the act, there are provisions that allow the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to create lists of species in need of protection due to trade in that species, and/or threats to its habitat. Once listed, a species cannot be imported into the U.S., exported from the U.S., or sold from one state to another without specific permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (federal).

Breeders or fanciers that live in the U.S. and possess a listed species do not need a permit for legally acquired birds unless they plan to sell or barter with the species across a state line. If a sale or barter is to be made, there are two types of permits that would allow such an activity: an Interstate Commerce Permit, or a Captive-bred Wildlife Permit. Even trades of like offspring across a state line do not require a permit. Breeders making even trades should include a letter on shipments of listed species explaining the details of the transaction.

Permit Contact: Dept. Of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Management Authority, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr. Room 212, Arlington, VA 22203 of Call: 703-358-2104

Exotic Species Listed under the ESA as of August 2011:

(For complete list see www.fws.gov; several cockatoos species have been proposed and may be listed in the very near future)

Parakeets and Conures:

Blue-throated Conure (Pyrrhura cruentata)

Golden Conure (Aratinga, or Guaruba guaruba)

Golden-shouldered Parakeet (Psephotus chrysopterygius)

Hooded parakeet (Psephotus disimilus)

*Scarlet-chested Parakeet (Neophema splendida)

*Turquoise Parakeet (Neophema pulchella)

Parrots and Others:

Bali “Rothschild’s” Mynah (Leucopsar rothschildi)

Cuban Amazon (Amazona leucocephala)

Imperial Amazon (Amazona imperialis)

Lear’s Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari)

*Moluccan Cockatoo (Cacatua molucensis)

Red-browed Amazon (Amazona rhodocorytha)

Red-capped Parrot (Pionopsitta pileata)

Red-necked Amazon (Amazona arausiaca)

Red Siskin “finch” (Carduelis cucullata)

Red-spectacled Amazon (Amazona petrei)

Red-tailed Amazon (Amazona brasiliensis)

St. Vincent’s Amazon (Amazona guildingii)

Thick-billed Parrot (Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha)

Vinaceous Amazon (Amazona vinacea)

*NOTE: although still listed under the ESA, these species no longer require a federal permit for sales and Interstate commerce. However, the State of New Mexico has a State permit requirement to breed, sell, and import them into the State of NM.